How a Welsh Alcoholic Created a Better TTRPG Village Than I

Or: I know the quest for granular realism is hopeless but dammit, if I could just... oh, never mind.

If you have not heard the original radio broadcast of Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood, produced in 1954 and featuring Richard Burton as First Voice, stop reading this and go and listen to it. Right now. I’m serious. Go here. I’ll wait.

Back?

O.K. Good.

The first thing to say is that if you didn’t find that masterful use of language, tone, metre and rhythm mesmerising then I’m sorry, but we can never truly be friends. I mean, I’m sure I’d like you and everything, but if you don’t thrill just a little to these words -

Only you can hear the houses sleeping in the streets in the slow deep salt and silent black, bandaged, night. Only you can see in the blinded bedrooms, the coms and petticoats over the chairs, the jugs and basins, the glasses of teeth, ‘Thou Shalt Not…’ on the wall, and the yellowing, dickybird-watching pictures of the dead. Only you can hear and see, behind the eyes of the sleepers, the movements and countries and mazes and colours and dismays and rainbows and tunes and wishes and flight and fall and despairs and big seas of their dreams.

- then you are a little bit dead inside.

But, leaving aside the literary appreciation, what Thomas achieved in this ‘play for voices’ is a portrait of a small Welsh coastal village in the middle of the 20th century that is rich, evocative, detailed, dramatic and real. It achieves these qualities not by revelling in exhaustive detail, but by the keyhole examination of a small number of households and individuals. It is a masterclass in how to use focus, shifting levels of attention and immediate characterisation to create the sense of a living settlement. This is an account of how I managed to forget those salutory lessons in the creation of a medieval TTRPG village.

A few weeks’ ago, Grim Jim reviewed a small-press publication of an OSR fantasy village on his YouTube channel and many of the comments that the review attracted were critical of the author’s decision to limit the number of NPCs. If I had to place a small wager, I’d say that few, if any, of those commentators had given much thought to writing such a document, and especially not one that could be used by GMs and players outside their home-brew games. Fewer still would have sat down to undertake such a project having first acquired some little knowledge of medieval European human geography, economics and sociology of the kind that could be used to underpin a conventional fantasy world. How do I know this? Because if they had, they would have been slower to criticize the author’s efforts. How, in turn, do I know this? Because, reader, I’ve been there.

Some information for context. A few years ago I discovered, to my eternal chagrin, that RPG Pundit had published Lion & Dragon, an OSR/D&D clone substantially re-worked to reflect ‘actual medieval role-playing’. Not only had Pundit had the temerity to do the thing that I was kinda, sorta, maybe, thinking of doing, the swine had even made the default setting a version of later 15th century England during The Wars of the Roses. Hey! That’s my period! Anyway… In the end, I decided that, to work through my grief, I would use the Lion & Dragon rules’ set to write a supernatural murder mystery set in rural East Anglia in the early 1450s. As part of this, I would need to create a village and populate it, and so I set about the task.

Walsham (medievalists who know their well-documented East Anglian villages will get the reference) was conceived of as a small settlement of perhaps 30 to 50 households with a church, a glebe cottage, a manor house, an ale house, a post mill and a scattering of substantial yeoman farms. Within this location were sprinkled various NPCs who, alongside some church and manorial documents, could inform the characters of the recent history of the manor even as the threat began to move against the villagers and, eventually, the PCs. As first conceived, this all worked well enough, and I ran it as a mini-campaign of 3-6 sessions with three separate groups who all seemed to enjoy it. Some day I might publish a revised version of the original scenario here. I think at this point I’m probably advised to ‘drive reader engagement’ by asking people to ‘comment if you’d like to see my adventure’ but sod that, I’ll get to it if and when I’m good and ready.

So I had a workable, atmospheric and, I thought, interesting Call of Cthulhu style investigative adventure set in the 15th century using a more or less conventional OSR mechanic. Then I made a terrible error.

You see, up until then I had, without quite realizing it, adopted Dylan Thomas’ model. I had populated Walsham with a series of - though I say it myself - arresting and dramatic NPCs, but had limited detailed descriptions to between eight and ten individuals. But now the madness descended on me. In one of my many, many, many abortive efforts to re-work something I had written with a view to eventual publication, I went back to my bookshelves and consulted the usual authorities on late medieval agrarian economics and society - Britnell, Postan, Dyer, Hatcher et al. But the fatal volume was Peter Laslett’s The World We Have Lost, the seminal work that began the labour of using parish records to uncover the history of the family, the household and the community (sic) of pre-modern rural England.

Armed with the product of this reading, I set about re-building Walsham as a ‘realistic’ late medieval East Anglian hamlet complete with a parish guild, artisans, apprentices, live-in servants, yeomen farmers, day labourers and landless peasants that were all interconnected - villagers related by ties of blood and marriage, alliances and feuds, secrets and scandals. Have you ever sat down and seriously contemplated how many arts and crafts are required in a more or less self-sustaining medieval settlement? The bakers and blacksmiths and brewers and carpenters and coopers and carders and spinners and fullers and seamstresses and scullions and sextons and potters and millers and and and… Consider for a moment also the tangled webs that are created as soon as one begins to take account of rates of mortality and re-marriage in pre-industrial societies. The nuclear family would be bad enough, but the skein of kin relationships in societies where half- and step- relationships are commonplace is exponentially more intractable. Then, with the realization that no village existed in a vacuum, I had to decide which villagers were born and bred in Walsham and who had come from surrounding villages, which necessitated yet another layer of complexity with people who brought into Walsham relationships and concerns from outside. So far, this was becoming frustrating and was already beyond anything that anyone could usefully bring to a TTRPG table. Then, not content with the monster I had created, I added yet another dimension: Time.

This is where things got truly, mind-bendingly, insanely, complex. It’s all very well knowing who likes or mislikes who, or who is the guild warden this year, who are the haywards, or who is married to who, or who is who’s mother or sister or cousin or uncle or bastard or lover as a matter of contemporary in-game fact. But it became clear that these facts could not be adequately explained (at least to my own satisfaction) without reference to what had gone before. Because villages are an agglomeration of stories and rumours and grudges and graditudes that are acquired over time and work themselves out through changing relationships and circumstances as the months and years roll past. In the context of a TTRPG, a medieval hamlet is a living world that characters come in to, explore and, if they so desire, act upon to change. Without a concept of history and its ongoing relevance and importance, Walsham would be no more real than Westworld. Or so I imagined.

Of course, it was lunacy. Within days I was having to maintain separate documentation for every household, with a system of cross-notation to allow me to keep track of the fact that so-and-so’s daughter was the live-in servant of such-and such. But the real revelation was that, while we tend to think of diminuitive pre-modern settlements as the smallest unit of social organization, they are in fact an accumulation of many other strands of interaction. In Walsham, quite apart from the familial, household and business connections, there was the parish with its church with its clergy and lay guildsmen, the manor with its great house and servants and functionaries, the ale house where the business of village officialdom mingled with gossip and rumour, the small coterie of Lollard heretics. Each of these was in turn further seamed and honeycombed with the social stratification of petty nobles, minor gentry, wealthy yeomen, farmers, labourers and peasants. And all of this had to be written down and taken account of in a single at once tiny but vast web of connections.

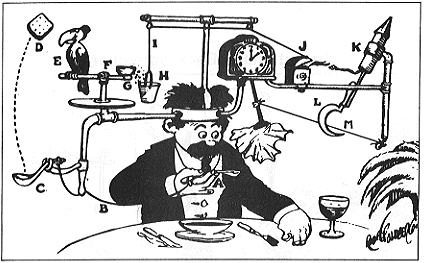

What I built was thorough, detailed, subtle, plausibly grounded in historical fact and utterly, utterly useless as a TTRPG product. It was a Rube Goldberg machine. If I, as its creator, couldn’t keep on top of it all as I was in the act of writing it, how on earth was a casual reader or GM supposed to? And so Walsham is filed away in a little sub-folder of nearly was and also ran projects. Never mind, it has plenty of company. I wish I could say that this experience was sufficient for me thoroughly to learn the lesson of the importance of brevity, lyricism, focus and selective emphasis that Dylan Thomas teaches so well in Under Milk Wood. But that would be to tell an untruth.

Come here. Lean in, and let me tell you about the scenario I’m writing set in a medieval monastery…