Habits of Mind and Why I'm Not Good at Running Sci-Fi TTRPGs

Or: For the love of god, give me something real to hang on to.

All GMs have one. Most (including me) have several. That time (or those times) where your game just sucked. And I’m not talking about those routine incidents where you finish a session and say to the players ‘Sorry folks. That one felt a little flat’ only for them to respond ‘No. It was good. I enjoyed it.’ Most players - being decent human beings - won’t, even when offered an opportunity to do so, tell the GM to his or her face that they did a bad job. In the eternal three-way battle between a desire to please, ego and impostor syndrome that seems to rage inside a lot of GMs (or is that just me?), one or other of the former two qualities often wins out, and a game will continue after a nominally dud session. In games that truly fail, much more common is the awkward, unstated, non-decision decision to just let it fizzle out because there is a concensus that something isn’t working, whether that be player or character dynamics, mismatched expectations of play style or that the GM has failed to bring a game to life. It is this last point that I want to focus on.

Last year I ran a sci-fi game. It was run using a fairly obscure system that included a setting that was - in many ways - a conventional cyberpunk world with the usual elements of biomedical enhancement, cybernetic improvement, corporate oligarchy and all the other familiar tropes. After three or four sessions, I had to cancel a session for some reason and, when it came to re-scheduling, I was vague about the date. I already had more than an inking that the game was holed below the waterline and this was only confirmed when the players, rather than chase me to put the next game in the diary, adopted a discreet silence. I should stress that the players in this game were drawn from a small on-line group of like-minded people, all of whom I rate very highly as role-players. They are committed and regular players who are not at all in the habit of flaking out or ghosting. But we had, as a group, allowed the game to expire and I think this tacit agreement to let it end was my responsibility. I had contrived to run a game that lacked focus, clarity and detail and in which characters existed in a poorly-defined and badly realized world. The cause was, I believe, a fatal collision between the way that my brain works and the nature of sci-fi as a broad genre.

Like Lord Flasheart, I desire something to hang on to when playing and running TTRPGs. If it is true (as I think it probably is) that the number of truly original ideas in any field of human endeavour is vanishingly small, and that almost all creativity is an exercise in re-packaging or re-combining existing elements into unfamiliar forms and expressions, then I am very far from unique in my lack of capacity for true originality. Where I do perhaps differ slightly is in my acute consciousness of the fact that, in the context of running and playing TTRPGs, I am a magpie. An epic kleptomaniac. To the extent that I have any useful talent for playing and running role-playing games, it is my ability to reach into my brain and drag up a person, place, circumstance or story beat that can be tweaked and teased into service as a plausible and sometimes interesting NPC, plot device, location or whatever.

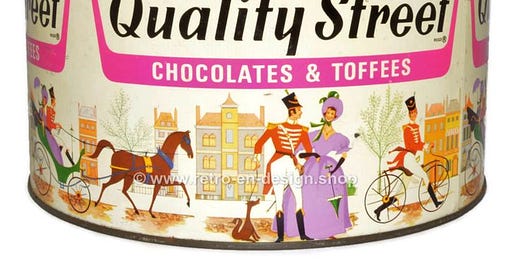

The sources of these inspirations can be from almost anywhere. Of course, as players and GMs, we all steal from conventional media all the time, and my own fascination with English history means that I have another store of information that I can draw from as needed. But I flatter myself that I have the ability to steal from almost anywhere and use the proceeds of this larceny to make descriptions of worlds feel real and substantial in sometimes wildly different contexts. A trivial example: In the U.K. there is a brand of chocolate called Quality Street that makes tins containing a selection of individually wrapped candies. The branding of these tins was for decades images of mid-nineteenth century figures of men and women - soldiers in red coats with elaborate headgear, women in bonnets and hooped skirts. I have used these images as the basis for describing passers-by in games of Cthulhu by Gaslight. Objectively, the Quality Street costumes are outdated by almost half a century in the context of describing a game set c.1890 but, as the basis for an account of what characters see when they walk down Shaftesbury Avenue in the summer of 1892, they lend an instant degree of plausible detail.

A more extended example. I am currently playing in a game set during the expansion of the city state of Babylon. I know absolutely nothing about that era of ancient history and so my store of strictly relevant information to call upon is barren. Yet I am extremely lucky that in this game - which consists of the GM, myself and one other player - we award ourselves permission to use analogies to fill in the details of the setting as required. In a game world that features the centrality of polytheism, the ubiquity of slavery and strict social hierarchy and the absence of so much material culture compared to later ages, we merrily skip along the aisles of our collective storehouse of knowledge, pulling examples from a wildly disparate array of sources to serve as a means of illustrating the world of Mythic Babylon. These have included the British empire in India, Reformation Europe, Anglo-Saxon and Victorian England, ante-bellum North America, imperial Japan and classical Greece and Rome. Each one is selected for its ability to illuminate some aspect of the themes of faith, caste, class and conquest as we feel our way towards an agreed and believable version of Babylon, its people and culture.

So why did my sci-fi game implode? Because I was unwilling or unable to use my familiar swag-bag of stolen goods to draw from to create a setting with the appearance of depth. It felt like an under-rehearsed play; a half-finished sketch; a story that had begun without any understanding of where it was headed. It was the role-playing equivalent of the arc of the T.V. adaptation of Game of Thrones (you’ve seen the meme of the drawing of the horse that gets progressively more incompetent… Yeah. That.) Yet what is the material difference between adapting examples to inform an ostensibly historical game and using the same process to make a sci-fi setting come alive? After all, our version of Mythic Babylon is no more real than Night City. I think the distinction lies in my own habits of thought and the way that my brain relies (too much) on using things that have actually happened to ground the creation of quasi-historical fiction, but rebels against using that same process for what the pulps used to call ‘speculative fiction’.

I should add that there are some science fiction settings that I am comfortable with. I’ve played and run Star Wars (WEG d6 and FFG) and Free League’s Alien, enjoyed them as a player and, as a GM, the games have been adequate. The reason, of course, is that these settings come with so much canon and lore and so many visual representations that they have something very like a sense of the real. For the same reason I would imagine (though I haven’t played it yet) I wouldn’t have too many issues with Free League’s Bladerunner. I’m also currently playing in a game set in the world of Cyberpunk 2077 that I am enjoying because I have a sense of the world (or rather, the other players and the GM fill in the blanks for me as we go). I don’t need to fret about so many of the kind of trivial details that I use to inject verisimiltude into my games as a player and as a GM, because the source material is so vast that there’s probably an answer (or a plausible answer). I have something to hang on to. But generic cyberpunk settings? Traveller? Eclipse Phase? I just can’t grasp the scale of those worlds.

Science fiction is limitless in a way that no other genre is. It doesn’t matter how epically high-fantasy a setting is, it is necessarily grounded in some aspect of the human past in order for it to be intelligible. By contrast, in sci-fi the past is no guide to the future because the creation or description of that future is the point of the genre. The massive consequences of those standards of the form - faster than light engines or time travel or radical genetic alteration or the detachment of mind from body - are incalculable and so potentially large as to defy quantification. This, of course, is its appeal; sci-fi allows authors, film-makers, game designers, GMs and players to cast off the cloying restraints of history. I have nothing but admiration and more than a little envy for those who are able to do that and, if I was feeling bitchily defensive, I might speculate about how much of science fiction actually achieves that escape velocity from our past and truly breaks new ground. In the end, my own habits of mind and thought allow me to conjure plausibility in some senses even as they curtail my ability to do so in others. Too late to do much about that now, but I do sometimes wonder whether I’m missing out on something.

100% agree, can’t do sci fi unless it’s tied to a specific IP, eg Judge Dredd or Aliens.