Medieval Law Enforcement in TTRPGs - Part Two - Trial

Last time in this series, we looked at how medieval England sought to control behaviour and, in the end, coerce adherence to law and order. Here we will be describing the form and method of criminal trials and how the historical reality can inform a quasi-medieval TTRPG setting.

The emphasis will be on the English system of justice as it emerged after the mid- to late-1200s and so we will not be examining the more ahem… arresting details of the methods of trial by ordeal or by combat that had largely vanished by the reign of the Plantagenets. I will not be discussing in any great detail the bureaucratic procedures that were used to secure a defendant’s presence in court (the so called mesne process) nor the strictly judicial processes of a trial because, fascinating as I find them, I suspect most RPG groups are not overly concerned to dig in to the workings of the writ habeus corpus cum causa or the judicial merits of the 1413 Statute of Additions (sorry, paywalled). However, where it intrudes on actions and situations that GMs and players might find interesting to explore, I will briefly address some technical matters. Nor will this be an essay on the entire range of medieval English criminal trial venues and procedures; rather, it will selectively examine a single example of the type of courts that dealt with progressively more serious crimes - the manorial courts, the quarter sessions and the King’s Bench and royal commissions - as broad models that can be inserted into a quasi-medieval RPG setting.

At the very lowest level of criminal trial venues were the manorial courts that enforced the rights of landholders and settled minor disputes between tenants. These venues were the single most common experience that medieval English men and women had of the law and the courts and it seems probable that an appreciable proportion of the entire rural population of the country ended up before a manorial court at some time in their lives. Manorial courts met usually every three weeks, presided over by the lord’s steward assisted by village officials such as the reeve and hayward, a clerk to record matters and jurors made up of local men. Attendance at all manorial courts was mandatory for unfree villeins and for a set number of court days per year for free tenants. Failure to attend without excuse attracted a fine (or amercement) in cash or kind. These courts were empowered to hear all cases of offences against the rights and dignity of the landlord, those matters that the crown might have granted the lord local jurisdiction over such as enforcing the rules around the production of bread and ale (the assizes) and matters of debt, detention of goods, seizure of land and ‘trespass’ between the tenants. Trespass was a slippery concept but basically amounted to any ‘harm’ to a tenant’s person, lands or goods that did not fit within the actions for debt, detention of goods and land appropriation and was not suffiently serious to warrant a full criminal trial.

Cases could be brought by the lord’s presiding official, by the jury of local men who reported (or presented) events that were worthy of the court’s attention or by individual tenants against one another. In the first two methods of prosecution, it seems that the odds were heavily against a defendant, probably because the acts were well-known locally and denial was pointless. Where one tenant complained against another, the odds were a little more even. Both parties were obliged to find ‘pledgers’ who would undertake that those involved would attend future courts and adhere to the requirements of procedure. In the event that either plaintiff or defendant did not show up to court or otherwise failed to engage with the process, the pledgers would be fined and the case would be thrown out or found proven depending on who had been remiss. If the case proceeded to trial, this would often take place after an inquest carried out by local men to assess the facts of the case and, if these were not clear, verdicts were decided by wager of law where the defendant - together with between five and eleven ‘oath-helpers’ - would swear their innocence. Those who were found guilty, as well as their pledgers, were amerced (fined) and held to be ‘in the court’s mercy’. The level of such fines was usually only a few pennies or perhaps shillings but, for a rural peasant, they represented substantial sums.

What made manorial courts effective was their deep roots in the region over which they presided. Information and obedience were secured precisely because all involved were neighbours who were intimately familiar with one another and the events that had taken place in the vill. Nor was this a one-way process that only favoured plaintiffs over defendants. Consider the case from the manorial court held in Walsham le Willows in October 1303, from which it seems that, for all the potential for oppressive small-town prejudice, local knowledge of one’s neighbours could be a useful thing for the accused.

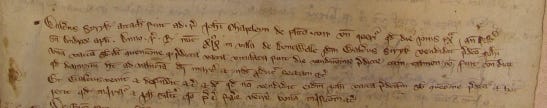

William Goche complains against Roger April concerning a plea of debt, and the said Roger finds a pledger to reply… And Roger is acquitted by Walter Wodebite and the other jurors, because William does not speak the truth, and therefore William is in mercy (amerced 6d).

R. Lock (ed.), The Court Rolls of Walsham le Willows 1303 - 1350 (Suffolk Records Society Vol. XLI, Woodbridge, 1998), p.29.

It would be unwise for a manorial tenant to use the lord’s court as a venue for the pursuit of a vendetta. The juries who presented cases to the court were selected from among the whole adult male population of the village and the membership changed from session to session in rotation, meaning that a malicious prosecution of a neighbour this week might lead to that same neighbour being on the jury at the next court and responding in kind.

In towns and cities, the approximate equivalent of the manorial court was the burgage court. Rather than the rights of landlords, these courts were concerned with disputes between burgesses and the sort of offences that arose when people lived in close proximity to one another and carried out sometimes noxious commercial or industrial processes. The burgage courts were presided over by elected senior townsmen such as a mayor and aldermen rather than manorial officials, but they too employed juries of townsmen to bring cases to its attention and deliver verdicts. They dealt with a similar array of cases using analagous procedures but tended to be more concerned with ‘quality of life’ offences such as dumping of rubbish in public spaces, dangerous neglect of buildings, the nuisance of noise and odour that resulted from smithies and tanneries, mis-selling of goods and blocking access to public thoroughfares.

As free-roaming adventurers rather than agrarian peasants, it is unlikely that any group of characters will be subject to the strictures of a manorial court. However, the workings of a manorial court provide GMs with a wide array of NPCs and low level story hooks in the context of scenarios that take place in rural society. For those more attracted to the intricacies of domain-building play, a PC who is himself a landowner can be introduced to his manorial court as at once a useful tool and a potential source of conflict. The manorial courts were not purely a rubber-stamp for the lord’s will and juries could just as easily frustrate a landlord’s ambitions as advance them.

We will pass over the next level of English local courts that had flourished since the before the Conquest - the sheriff’s tourn, the County and the Hundred Courts - as, although they retained some importance as procedural venues (outlawry had still to be proclaimed in the county courts) these had, by the later 14th century, been rendered largely secondary as trial forums by the emergence of the system of Justices of the peace which dominated criminal procedure for the next six centuries and to which we now turn.

Justices of the peace (JPs) were commissioned by the crown for each particular county and were drawn from the ranks of local knights and gentry. They were to serve until such time as a new commission was promulgated. Initially, these justices were laymen selected for their local power and influence but, as time went on, an increasing proportion of judges and local professional lawyers were commissioned. Generally, very senior nobles did not sit as JPs but, in times of serious disorder, they could be named to a county commission to reinforce the ability to compel adherence to its orders. So important were the justices and the work that they did that, in times of extreme political disorder, the commissions were subjected to manipulation and influence as local or national factions sought to stuff them with favourable partisans. One can trace through the changing names of the JPs the varying fortunes of the houses of York and Lancaster during the crucial years 1459-61 as each side sought to re-cast local law enforcement to its own advantage.

Over time the justices’ courts settled in to a routine of meeting four times per year at so-called ‘quarter sessions’. Because most professional judges and lawyers needed to be at Westminster during the formal law terms, JPs sat outside the days set aside for the working of the central courts. These sessions were actually a series of courts held at various places in the county, sometimes sitting for days at a time, sometimes for only a few hours before moving on to the next venue. The justices and their staff of clerks sat in public and, using a list of ‘articles’ to be investigated, took information from local officials, juries and individuals. This meant that, at any given quarter session, there could be hundreds of people present in their various capacities as local officers, jurors, plaintiffs, defendants and witnesses. The information gleaned was worked up in to formal ‘bills of indictment’ that set out the alleged offences against particular people. The range of offences that the JPs could try was extensive and ranged from the serious crimes classified as ‘felonies’ - murder, rape, arson, robbery, burglary and high value theft - to misdemeanours such as assaults, minor thefts, breaches of the assizes of bread and ale and ‘economic’ crimes such as forestalling and regrating (buying up goods with a view to securing a local monopoly and increasing prices) or seeking to evade the various laws to hold down wages and limit the free movement of labour enacted after the Black Death. Having drafted the bills of indictment, the justices instructed the county sheriff to secure defendants to answer any charges.

Usually, the sheriff would attempt either to arrest the suspect and hold them in custody (attachment by body - capias) or seize personal property that would be forfeit if the defendant did not attend court (attachment by goods - distringas). The single greatest difficulty the justices had in securing suspects was that a writ of arrest or distraint was issued to a sheriff of a given county and could not be enforced outside the boundaries of that county, which allowed defendants to simply remove themselves or their goods from local jurisdiction. Another problem was that, when most criminals who appeared before the justices were poor, they had few if any goods that could be seized. The result was that the most common shrieval reply to writs was either ‘non est inventus’ (he is not found) for writs capais and for distringas ‘nihil habet’ (he has nothing). In practice, as England had almost no capacity to hold large numbers of prisoners for weeks or months at a time, even those who were attached by body were very often bailed, they or their associates undertaking to pay a sum of money if they failed to show up for a later hearing. If a defendant repeatedly failed to come to court, they could be proclaimed an outlaw. In theory, this meant they were outside the protection of the law and could be killed without consequence. In practice, certainly by the fifteenth century, this was almost unheard of and outlawry was a substantial inconvenience more than a dire threat.

The crown was represented by a prosecuting attorney at trials that took place before panels of local juries who reached a ‘true saying’ (veredictum) as finders of fact and the justices acting as judges who passed sentence. As with all criminal trials in England, the defendant was not permitted to be represented by legal counsel save in those rare instances where the court allowed that a question of law (as opposed to the strict facts of the case) arose. A defendant could seek to argue that there was some material defect in the indictment such as an incorrect identification of some party or an error as to the date or place of the alleged offence. By the later medieval period what had once been procedurally valid loopholes to escape prosecution had largely been closed, with case law severely limiting the grounds for dismissal based on inadequacy of the record and indictments phrased more elastically to allow for some wiggle-room with the use of phrases such ‘on or about’ a particular date or defendants listed as ‘so and so, also known as such and such’.

In the vast majority of cases, a poor suspect’s only option was to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty to the charge. An accidental consequence of Lateran IV’s banning of trial by ordeal and by combat in 1215 was that English law retained the old notion that a defendant must consent to entering a plea and being tried by jury. Obviously, a suspect could not be permitted to derail the entire process by witholding his consent to ‘put himself on the county’ as the phrase had it and, for this reason, there emerged the notion of persuasion pein fort et dure (‘hard and forceful punishment’) whereby anyone who refused to plead was subjected to close confinement on limited rations or, in extreme cases, pressed beneath increasing weights until he assented or died. For the wealthier or better connected, there was a system that allowed them to defer entering a plea and instead seek a writ to have the case moved to the central royal court of King’s Bench, in part because this always led to delays but also because the court was more inclined to hear arguments of legal or procedural error than the local justices.

Because the quarter sessions were not ‘of record’ (they did not deal at all with disputes over ownership of land that had to be recorded for future reference and their rulings did not create binding precedents) their files were very often destroyed after some years as they had no long-term value. This means that many of the quarter session records for the later 15th century are lost, save where a file of cases was sent up to the royal courts or was preserved for other bureaucratic purposes. No-one really knows the extent to which this gap in the records has obscured or distorted our knowledge of the actual workings of the English JPs. We have less information than we would like on how late medieval juries at quarter sessions decided cases before them. In later years - particularly from the 18th century - we have strong evidence to suggest that jurors would ‘sabotage’ criminal trials to avert what were seen to be miscarriages of justice. Jurors in the 1700s seem to have deliberately found as a matter of fact that the value of stolen goods was below the threshold that would result in a capital offence. We have good reasons to suspect that medieval jurors at quarter sessions indulged in similar behaviour and I will be looking at this in more depth in a future post about punishment but, because accounts of so many cases of such little contemporary merit or interest do not survive, we cannot be certain of the exact process at work.

The highest criminal court in the land (other than Parliament acting in its judicial capacity) was the Court of King’s Bench (or the of Court of Queen’s Bench if the monarch was a woman). In legal and constitutonal theory, trials in the King’s Bench were technically held ‘before the king’ (hence the alternative name for the venue - coram rege) and any disrepect to the court was a species of lèse-majesté. Soon after he came to the throne, Edward IV had a man’s hand amputated as punishment for striking a justice of the King’s Bench. Staffed by senior professional judges, by the mid-15th century the court, which had once been peripatetic, had settled permanently in Westminster Hall and received cases sent to it either by the justices of the peace or in response to writs sued out by plaintiffs or defendants for a change of venue. It could also move cases to its own jurisdiction of its own motion. King’s Bench had the authority to rule on any criminal matter and its decisions could only be appealed through a direct petition to the monarch. The decisions of the King’s Bench were ‘of record’, meaning that they could be applied as precedents in similar subsequent cases. This is why we have such a long and unbroken series of court ‘rolls’ (actually, they are a series of parchment sheets c.12” wide and 3’-5’ long stitched together at the top) recording the actions and decisions of the court.

In many ways the procedure of the King’s Bench mirrored that of the quarter sessions. Like the JPs, the justices of King’s Bench sat at fixed times during the year. The four legal terms (Michaelmas, Hilary, Easter and Trinity) demanded the presence of judges and lawyers in Westminster, which was why the quarter sessions took place outside these dates. Like the quarter sessions, the King’s Bench employed the machinery of writs of distringas and capias to secure defendants (and with the same limitations). The King’s Bench did, however, have the advantage of having its own dedicated prison - The Marshalsea in Southwark on the south bank of the Thames - to which it could remand prisoners in custody pending trial. Defendants could seek bail from the custody of the King’s Bench and it is clear from the records that here was another area of English law in which everyone connived at a fiction. When one examines the names of the supposed ‘mainpernors’ who undertook to have a suspect in court, one soon comes across such implausible entries as ‘Richard King and John Queen, Hugh Rust and Thomas Bust’ or ‘Robert East and Martin West’. The sums of money that had to be forfeited in the event of non-appearance were probably real but, whoever was actually liable to pay up if the suspect failed to appear, it certainly wasn’t this group of fancifully named individuals.

Until 1421, King’s Bench routinely travelled the country on circuits whereby it visited a series of counties and called in to its jurisdiction all serious cases that were pending - the defendants having been indicted at a previous quarter session - as well as issuing indictments based on information received upon it arrival in the locality. This process of sending powerful panels of judges out in to the regions to deal with crime was a regular feature of English law enforcement for centuries. Before the the peace sessions emerged as the default venue for local criminal trials in the second half of the 14th century, the crown had relied upon the procedure known as the Eyre. The Eyres (which could be General, tasked with looking in to all local offences and disputes, or Special examining only a limited number or type of cases) had, by the early 14th century, become weighed down by the sheer range of business they were required to deal with, visitations taking longer and longer as the workload increased. Edward III began the process of replacing the Eyre, first with a series of ad hoc commissions such as those called trailbaston that were raised to visit particular places and investigate and try cases. Like the quarter sessions, these were staffed by a combination of local landowners and professional lawyers of the kind who moved in to dominate the justices of the peace when they became established as the replacement of the Eyre.

Even after the establishment of the quarter sessions, commissions were issued and those named on them empowered to traverse the country and conduct judicial business. Regular commissioners made up of senior lawyers and judges were sent out to try the most serious cases of suspects gaoled by the quarter sessions - hence their title of Commissions of Gaol Delivery. Less common, but more fearsome, were those commissions to ‘hear and determine’ (oyer et terminer) serious or high-profile instances of disorder. These powerful bodies could be promulgated by the crown to conduct a public law enforcement campaign in a given region but could also be created by the monarch at the request of a private individual or as a result of a parliamentary petition from local MPs. The commissioners were chosen to maximise the chances of the successful investigation and prosecution of disorderly local elements of society, with the most powerful trustworthy local landowners accompanying the most senior judges. One of the most well-known of these commissons was that sent in to Derbyshire in 1468 to get to the bottom of a series of violent disputes between local gentry and which employed prosecutions under the statutes against unlawful livery to apply pressure to all sides.

One further method of trial deserves brief mention. As mentioned above, in 1215 the Lateran Council forbade the use of trial by combat in Christian kingdoms and, in large part, this prohibition was respected in England. The one exception were the processes of ‘the appeal of felony’ and ‘approval of felony’. The first form of appeal was a private prosecution brought by the family of the victim against the suspected felon and it was open to the aggrieved party to demand that judgment be given after trial by combat. This archaic process would - technically - be legal until its formal abolition by statute in 1819 but its use seems to have been extremely rare. In the one or two examples I came across during my own research for the period c.1459-85 it was almost always used to get a case into the royal courts before the ‘appeal’ by the wronged individual was abandoned (attracting a small fine) and the case was taken up by the crown as a normal criminal prosecution. The second form - the approval of felony - was the precursor to what would become known as ‘turning state’s evidence’. In these instances an accused felon could escape conviction, be held in gaol and even allowed a small daily stipend from the crown for as long as he was able to name other felons who were successfully convicted. In 1455 Thomas Whitehorn was arrested in Winchester for theft and went on successfully to accuse (approve) 18 men of felonies. His run of good luck came to an end when one of those he accused opted for trial by battle, at which Whitehorn was defeated and subsequently executed.

Why do so many quasi-medeval TTRPG settings lack any account of crime and criminal process? True, even the most accessible source material is often technical and the whole subject rarely seems to lend itself to dramatic story-telling (which is odd, given the enormous and consistent popularity of ‘court room drama’ in other media). But I think the major reason that many medieval RPG settings do not emphasise the importance of criminal justice is because of the inherent loss of agency once a character becomes ensnared in its procedures. Any GM with enough experience will have their own horror story of how that great idea they came up with to throw the party into prison turned into a grinding chore that was only resolved by some clumsy and unsatisfying deus ex machina that allowed the characters to escape. But the reality in medieval England was that even those accused of the most serious crimes were very rarely imprisoned either before trial or as a punishment afterwards. England did not have the capacity to gaol large numbers of people and characters accused of crimes up to and including murder can reasonably expect to be bailed in a faux-medieval world.

While this seems to resolve the agency problem, it actually introduces another: lack of consequences. Why bother introducing the criminal justice system into your setting when characters can, in effect, walk away from even the most serious offences? The solution to that can only come through the inclusion within the world of a sense that the actions of characters have consequences that manifest in play. A sufficiently powerful or wealthy character who commits murder might be able to forestall the criminal process almost indefinitely, but in any remotely plausible medieval setting he will be relentlessly pursued by fear and mistrust in all his dealings with the law-abiding. Merchants will not sell him goods, apothacaries and physicians will balk at aiding him, no-one of importance will have him under their roof. These in-game consequences and their capacity to generate new stories only make sense if the setting has an account of the workings of the criminal law that exist in the world.