Medieval Law Enforcement in TTRPGs - Part One - Discipline

As a diligent low-status player, when I was undertaking my doctorate and met people for the first time, I was always careful to warn my interlocutor that, no matter how much they thought they wanted to know about my research, I had to assure them that they really didn’t. Yes, The Wars of the Roses and crime and the law certainly sounds interesting (and it is), but whereas most people would want to know some shiney antiquarian factoid (and, believe me, no-one loves an antiquarian factoid more than I) at the time I was more likely to launch into an excrutiatingly technical description of the workings of the writ latitat or the fictitious use of the procedure of voucher to warranty to conceal transfer of leasehold tenure. Even now, a decade and more after I have left academia, it is going to be an effort of will for me to stick to the point of this discussion and not get lost in the weeds of narrative and technical details. Because this is about my first and abiding interest: the question of how late medieval English society (and therefore quasi-medieval fantasy worlds) enforced the law and ensured order.

How do you enforce the law when there are no police? No standing army? It was a question that fascinated the Victorian and Edwardian historians of England who lived in a country where both institutions were regarded as indispensable to the idea of a civilized nation-state. The answer they commonly arrived at was ‘Not well’. As the unequalled number of surviving medieval English legal records were recovered from their filthy canvas bags in the Tower of London and centuries of black mould removed from the parchment, these historians uncovered a mountain of material describing homicide, riot, theft, assault, trespass and fraud.

What these historians were labouring under was a form of observer bias derived from two factors. First, they worked under the general contemporary presumption that, without a police force, it was almost axiomatic that crime would be rampant, save where it was held in check by the corrupt power of the ‘over-mighty’ nobility. Second, they did not fully realise that the sheer richness of the available sources in themselves influenced the conclusions drawn from them. If you spend years poring through the records of the civil and criminal courts, reading daily accounts of medieval men and women at their worst, it is hardly surprising that one comes away with a dim view of the ability of the English to behave themselves. The first misinterpretation was remedied through a re-evaluation of the system of ‘bastard feudalism’ and the work of anthropolgists and sociologists who examined the question of the informal enforcement of social conduct and just how effective such mechanisms can be. The second issue was more stubborn (and, indeed, still persists in some quarters), but was partially addressed by framing the conceptual question the other way about. What if, instead of ‘crime waves’, the legal records reflected ‘enforcement waves’ as royal government actively sought to enforce order? Instead of uncontrolled violence and chicanery, what if the huge number of court records revealed a people clamouring to use the law to resolve disputes?

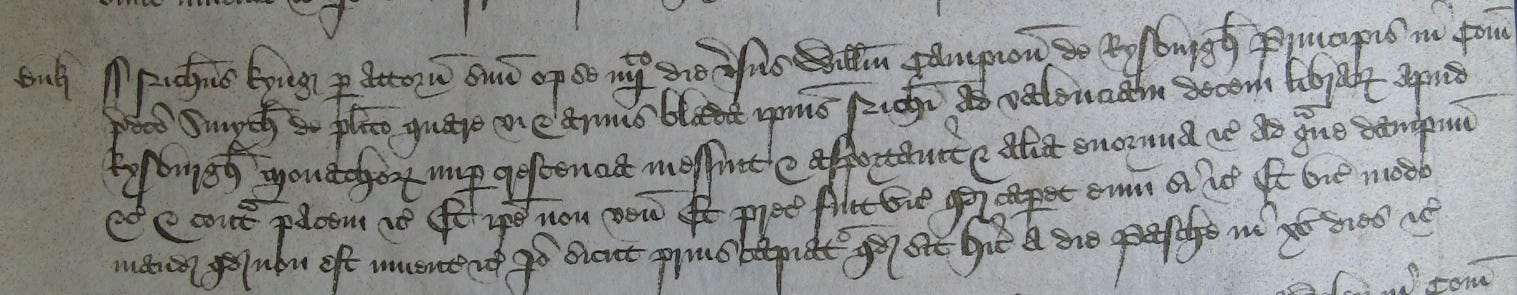

To this was added the growing appreciation of the technical uses by which fictions were employed for litigious advantage. In the case of King v Campion, above, it might look like phrases such as ‘with force and arms’ and ‘against the peace’ indicated violent action. In reality, in order to get a case in to the Common Bench (desirable because the court could issue arrest warrants for any county and give definitive and binding verdicts of record), a plaintiff would need to frame the case using that form of words to establish it was one of ‘trespass vi et armis’ over which the court would accept jurisdiction. In reality, it is at least possible (perhaps even probable) that the underlying facts of the case - entirely buried under the form of pleading - amount to a contractual dispute over the sale of grain. In the King’s Bench, where criminal trials were conducted, the records of assaults are rendered more exciting by the long list of weapons employed by the participants (‘a bow and arrows, value 4d, a cudgel value 1/2d’). This sounds dramatic until you understand that the clerks of the court were entitled, upon conviction, to the value of the listed weapons as part of their fees and, as time wore on, these accounts probably became pro forma and bore little relationship to what actually happened. I did warn you that I might not be able to resist getting dragged off down a rabbit-hole.

The lessons learned from sociological and anthropological studies of agrarian societies came to inform our understanding of how medieval England policed itself. The ‘mafia’ culture of the Mediterranean and the ‘frontier’ of the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries provide singularly useful analogies. What these studies revealed was the extent to which static, small communities (sic) were capable of enforcing codes of acceptable social conduct. In a village where everyone knows everybody else, and almost all economic and social activity is, if not strictly collectivist, then at least dependent on co-operation, ostracization can be extremely damaging, if not fatal. Almost as much as the Victorians, we still marvel at how trials could be decided by swearing an oath. But this is to reckon without the vital importance of reputation. Trial by oath was not simply a religious phenomenon, it was also a public affirmation of the suspect’s standing in the community, sometimes given very visible expression by being able to call on multiple ‘oath helpers’ prepared to swear on behalf of the accused. Your word was only as good as your esteem in the eyes of your neighbours, and who were better qualified to judge? To our modern sensibilities, this feels like a recipe for injustice, but medieval society was supremely comfortable with the fact that the probability of guilt and the depth of culpability were inextricably linked to one’s social status, because status was part of the divinely mandated social order.

Nor could it simply be a case of moving away and starting again, because to flee was to unplug oneself from the networks of support and obligation that ensured prosperity and survival. A stranger was always a source of suspicion. When a party of armed and travel-stained adventurers turn up in a hamlet in your quasi-medieval fantasy setting, they will be the objects of fear and doubt, constantly watched and assessed. Having no ties to the locale, such figures lack both reputation and the social connections that can serve as pressure points to be squeezed to ensure good behaviour. Agrarian peasants were neither bovine nor passive; they could be ruthlessly brutal and had weight of numbers, common purpose and plenty of sharp or heavy implements in their favour. Consider the account in Laurie Lee’s Cider With Rosie of the obnoxious villager who returned to Slad after many years to boast of his fortune made abroad, only to be murdered and the village to close ranks to prevent the case being solved. And this in Gloucestershire in the early 20th century. The Coroners’ Rolls of medieval England are strewn with accounts of the homicide of strangers for which the local juries have - seemingly - no explanation. Indeed, the very word murder descends from the Norman innovation of the ‘murdrum’ fine levied against whole English communities who refused to provide an account of the death of a Norman. GMs should perhaps ponder what might be the fate in their fantasy world of characters who threaten the local alehouse keeper with violence…

Sitting alongside this informal system of behaviour modification were more structured methods of communal law enforcement. The Anglo-Saxon system of Frankpledge continued well after the Conquest. Under this arrangement, households were organized into groups, each member of which was obligated to tell local or visiting officials not only of any criminal acts committed by strangers, but of any such behaviour within their own tithing of families and neighbours. Failure to do so rendered the entire coterie of pledgers liable to a fine. In even the smallest village some shrewd and competent man would be selected to serve as the constable with a public duty to investigate low level offences and the power to call upon his neighbours for help in securing malefactors, help that would almost always be forthcoming from a community with a profound self-interest in the maintenance of good order. In larger settlements, where social bonds were necessarily looser, there was a general duty to raise ‘the hue and cry’ against anyone seen committing a crime, whereby all men were expected (again, under penalty of a fine) to chase a suspect and secure him for questioning. In medieval England, when most people carried the small knife called a ‘whittle’ and men were required to train with the longbow, a hue and cry could be much more dangerous than a running brawl in the streets.

Of course, your party will almost certainly be rootless adventurers and so not for them the oppressive conformity of village life and community (sic). But the medieval English were not without recourse to mechanisms of ‘public’ policing. Victorian and Edwardian scholars had great difficulty with the concept that the state did not enjoy a monopoly of violent coercion and that private power was what actually underpinned the public enforcement of the law. I will here resist the temptation to slide down another rabbit-hole on the supposed evils of ‘bastard feudalism’ and why its causes and consequences were so badly mis-understood for so long (‘Stay on target! Stay on target!’). Instead, I will confine the discussion to what happened when serious disorder - of the kind that a particularly powerful or egregious group of characters might cause - occurred in later medieval England.

Despite the often successful effort to rehabilitate the English medieval system of peace-keeping, it remains that case that, from time to time, there were serious outbreaks of violent disorder. These incidents were almost always associated with structural political weakness at the centre (i.e. the monarch was not doing their job) or instances of defects of personality among individual local lords (such as the Duke of Norfolk’s intemperate feud with the Paston family in the 1460s), but the focus here is not the ‘why’ of disorder, but the ‘how’ of its supression.

To be a ‘good lord’ was to offer support and aid to those who looked to you for advancement and protection from the wider world. A substantial land-holder possessed the social connections and resources needed to find jobs and positions for his clients or to shield them from the machinations of rivals. This was perfectly acceptable - even laudable - and no-one batted an eye at what would now be regarded as the grotesquely corrupt exploitation of personal networks of favours and obligations to secure personal and professional gain. If one were facing threats to one’s security and prosperity, the natural and logical course was to appeal to the local lord for aid in return for a promise of good and loyal service. In dire cases, this assistance could include calling upon the land-holder to place his men at your disposal. Historically, the ability of a landlord to call men to his service was the result of the direct feudal notion that tenants owed their lord military service. In the later Middle Ages this tenurial basis had been diluted and service could now be rendered in exchange for wages or some other favour with terms agreed in a written ‘indenture’, hence the term ‘identured retainers’. As a sign of this relationship, the lord would distribute to his retainers clothing in his colours or a badge of his heraldic device - the ‘livery’ that so exercised the early critics of bastard feudalism.

With no police or standing army, the power of local lords to raise groups of armed men was the only means of bringing serious malefactors under control. This might seem like a recipe for anarchy and bloodshed, but that would be to neglect the fact that a crucial justification of a lord’s power was its ability to ensure peace. A lord who abandoned that requirement was unlikely to secure loyalty, with the result that his power was undermined, and a man who could not provide protection and advantage to his followers was useless. This was not an ideal position to be in in an ambitious society where, just below any regionally dominant figure, were a host of lesser men ready and eager to take his place in the local political community. So if your adventuring party rocks up to some region and starts bullying and harassing the locals, it won’t be long before the local lord is beseiged by requests to gather his men in sufficient numbers to restore order and will, if he is wise, act upon those demands.

The same basic mechanism was also at work in more overtly public operations of the law. The king, as the ultimate ‘good lord’ was supposed to guarantee the peace and security of the whole realm but, absent any standing army, medieval English kings had no choice to but to rely on the power of the nobility and gentry to call out their liverymen in the service of the common good and public authority. At the lowest level of day to day enforcement this meant that the county sheriff was empowered to recruit men as ‘the power of the county’ (the posse comitatus) to provide the manpower necessary to affect an arrest. Evidently, the sheriff’s chances of success were improved if he could call upon the private retainers of the local lord to serve in a public capacity. For cases of truly serious strife, the crown would commission senior local lords specifically to arrest malefactors who had been able to ignore or escape the conventional local response from the sheriff. In the most intractable cases, a duke of the realm might be commissioned and, because of the nested structure of client and patron relationships, the duke could call upon earls, who could in turn call upon barons who could in turn call upon knights and gentlemen. In this way, just about every significant figure in large areas of the countryside could be enrolled in the effort, the private bonds between lords being exploited to further the needs of the commonweal.

It is important to note that the pressure of behavioural expectations applied all the way up the rungs of the social ladder. As much as the humblest village wastrel could be pressured by his neighbours to mend his ways, so landlords and their gentry clients were subject to the expectation of their peers that their political and social role was to maintain peace and amity. Contrary to the common assumption that they chafed constantly under a desire to assault their rivals, medieval English nobles, knights and gentry went to great efforts to avoid violent confrontation. One need not be dewey-eyed about this. An English landholder’s incentive to avoid trouble was grounded on their self-interest in avoiding strife that could spiral out of control as much as any high-minded yearning for peace. The result was the consistent use of informal arbitration between rivals who were compelled to enter into more or less informal negotiations and abide by the conclusions. Crimes up to and including murder could be arbitrated, the demands of criminal justice being satisfied by a collusive legal action between the parties to find the perpetrator ‘not guilty’ or guilty of some more minor offence. The reliance of both sides to a dispute on their masters’ continuing patronage was leveraged to pressure them into conformity. This too was applicable all the way up the social scale, as shown by the famous ‘loveday’ of 1458 by which the magnate rivals around Henry VI took part in an elaborate gesture of reconciliation that was, I suspect, more than somewhat pressed upon the antagonists by their own clients and retainers, fearful of the potential for anarchy if the divisions were not assuaged.

From the meanest peasant to the greatest noble, medieval English society had a sophisticated and effective machinery for imposing order. The mechanisms could be as informal as gossip and dark looks in the alehouse or a discussion between gentlemen to resolve issues quietly outside the courts. Where social conformity proved inadequate violence was most certainly an option and could take the form of an anonymous beating in a country lane or the summoning of large numbers of armed and armoured liverymen bearing the full authority of the crown and nobility of the realm. Small wonder that England in the Middle Ages did not suffer from the phenomenon of ‘the murder hobo’ and why, in a quasi-medieval fantasy setting that uses history as a template, they should be rare in the extreme.