The Illusion of Reality in TTRPGs - A Conman Confesses

Or: The merits of surface glitter over serious substance.

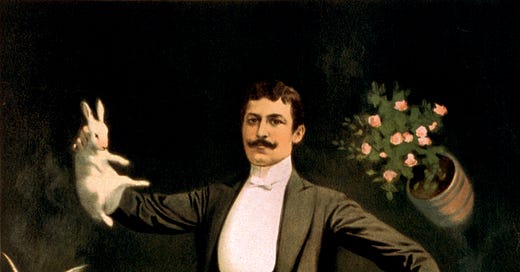

I have an abiding interest in magic - by which I mean the modern art of stage trickery and close-up sleight-of hand. I am not remotely competent at it as a physical discipline. I can palm cards and coins or deal cards from the bottom of the deck if pushed to it and, given time to prepare a pack of cards or the opportunity to make use of the many ‘gimmicked’ decks that are available, I could give a random spectator a mild thrill. But I lack the capacity for the sheer relentless grind that goes in to perfecting the dextrous craft of the true conjuror, and anyone with more than the most trivial knowledge of the form would find my efforts risible. What sustains my interest is not the performance per sé, it is the psychology of magic and what its practice teaches us about how we think. Also, in all candour, I am sufficiently tricksy to find the disparity between the outward glamour of a trick and the mundanity of its rather shabby reality amusing.

One of my favourite (and possibly apocryphal) tales about magic goes as follows. For many years a magician toured with an act that featured a card trick. In the trick, the magician would ask a member of the audience up onto the stage, helping them up from the well of the auditoreum. He would then hand them a brand new deck of playing cards, still wrapped in cellophane. Handing the deck to the member of the public, the magician would walk to the other side of the stage and turn his back before asking his ‘assistant’ to unseal and open the pack, pick from it a random card and keep it concealed from the magician’s sight. The performer would then correctly identify the card, much to the amazement of the audience and the on-stage helper. Those of you somewhat familiar with the techniques of the form might be thinking along the lines of conventional mechanics - the audience member was a ringer, the deck was rigged, some means was set up to allow the magician to see the card selected and so on. Nope.

The truth was at once more prosaic and stunningly insightful. As the magician helped the audience member up on to the stage, he took the opportunity to whisper to them ‘Please choose the nine of spades’.

Right now, I imagine that a certain proportion of readers are chuckling with amusement while another section are feeling slighly deflated and short-changed. Is that it?

But consider the true genius of that trick. Because what it relies upon entirely is the confidence the magician had that, on the vast majority of occasions, a random member of the audience for a magic show will connive at the working of an effect. Note the fact that the assistant even mimicked being astonished that his chosen card had been identified for the benefit of the rest of the crowd. Did the audience member collude out of a sense of social pressure so as not to ruin the show? Did they enjoy being ‘in on the gag’? It scarcely matters. The point is that it shows a profound understanding of the habits of thought of people taken as a group and the wit to find a way to leverage it in service of a few seconds of entertainment.

As a GM and player of TTRPGs, I am a conman. A charlatan. A cheap trickster. I offer the illusion of depth and complexity, the simulacrum of detail and truth. But it’s a lie. My worlds have no more depth than the painted flat scenery of a provincial stage play. My characters (and NPCs) have no more life than garishly painted marionettes. My contention is that this doesn’t matter in the least, because the most important thing at the table is not the actual depth of knowledge or feeling, it is the illusion of those things employed in the service of creating moments of interesting and perhaps even memorable role-playing experience.

My style of GMing and playing emerged as a result of the accident of my continuing teenage TTRPG experience. Jay, the American kid with whom I played my earliest games of AD&D, moved away when I was perhaps 16 and Geoff, the USAAF pilot who was our regular GM, was redeployed back to the United States at around the same time. For maybe a year I had no-one to play with until, entirely by accident, I was introduced to a group of people perhaps 6 to 10 years older than myself. In defiance of all the odds, this group of actors, musicians, performers and ne’re-do-wells had pitched up in my small East Anglian market town, where they began to attract a group of local waifs and strays that included me. They were unconventional, slightly louche, kind, idealistic, eccentric, acerbic and creative. And they played AD&D. I mean, what were the chances? Within weeks I was running all-night games for them in a small cottage owned by two brothers. The fact that I was supposed to be in school the next day was of no account.

Up until that time, my experience of RPGs had been strictly vanilla. Jay and I made characters (which, in all honesty, were just buckets of stats and mechanical gubbins) and Geoff presented us with a scripted adventure. I have very fond memories of playing The Sentinel and The Gauntlet at Geoff’s kitchen table. But here was something entirely different. These bastards just would not stay on the script! Every convention of play that I had absorbed - immediately bite on the story hook presented; swiftly narrate interactions with NPC plot-givers to get to the action; act vigorously and almost always violently to resolve any obstacle; play ‘characters’ to their best mechanical advantage - were torn up with glee as the characters bickered and schemed and wandered off to pursue other avenues of activity that interested or amused them without caring a fig for the plot or whether their stats or abilities made their decisions ‘optimal’. I had two choices; become frustrated that they weren’t ‘playing the game right’, or find a way to embrace this anarchic and unstructured approach. I unhesitatingly opted for the latter.

At first I adopted the ‘maximum prep’ strategy. If I gamed out in my head the players’ probable actions and reactions, I could draw up contingencies ahead of time and prepare material accordingly. This was, of course, a fool’s errand and I still blush slightly when I recall how long I doggedly persisted with this inadequate technique despite clear and obvious evidence of its lack of efficacy. Any group of players who know they have meaningful agency will confound a GM who relies on specific and detailed preparation - let alone a group of players who are ingenious, irreverent or just downright contrary. I cannot claim that there was any conscious moment of realisation or a singular instigating event that persuaded me to change course. The process is almost entirely opaque to me now precisely because it was gradual and emergent but, by c.1991, I was running what we would now call ‘collective storytelling’ games.

A Brief Word About Storytelling (eurgh)

Storytelling is a word that is, among a certain segment of RPG players, spat out with no little degree of contempt. To the extent that they are taking issue with the GM as a frustrated novelist, railroading his players along the tramlines of a story that only the GM wants to tell, I would agree with that sentiment. However, collective strorytelling is an entirely different concept, with the emphasis as much on the first word as on the second. Players and GM co-operate in driving a plot forward or even changing its focus and direction. The process is one of carefully calibrated negotiation and often one that happens without any formal discussion, just through the unstated assent of the whole group to some proposed action which creates another avenue of group or character activity.

We would later come to realise that this was a particular thing called improvisation (this was almost a decade before Whose Line is it Anyway aired and The Second City was almost unknown outside the U.S.) and we would also understand that it had, if not ‘rules’, then at least useful ‘techniques’. But, at the time, I was a rookie GM having to develop a way to respond to my players.

This is not one of those ‘How to be a Great GM!’ posts. Its purpose is not to provide a long list of improvisational techniques which GMs and players either already value, know or intuit or don’t. It is a discussion not of ‘how to’ but ‘why do’.

I think it is in Three Uses of the Knife that David Mamet records his skepticism about method acting. What does it matter, he argues, if an actor playing a wife pleading with a monarch to spare the life of her husband somehow generates the appropriate internal emotional state of fear, desperation and hope? It might be useful, it might even be an admirable skill, but it is irrelevant when measured against the entire purpose of a performance: to convince an audience of a character’s state of mind. An actor can generate within themselves the finest, deepest, most nuanced, true and profoud mental state of a terrified wife begging a king for mercy, but unless that condition is manifested outwardly for the benefit not just of the audience but for ‘the king’, it’s just a waste of time.

The same holds true for RPGs. Who cares if your latest character has a mysterious past or a dark secret or a great destiny or an unsettling weakness if those qualities are never given expression in play? For GMs this demand is even greater because their role is not to present a single character, but the whole world. You can have the most refined, granular, realistic and detailed quasi-medieval fantasy village (you probably won’t) but all those carefully collated notes and maps and diagrams are pointless unless and until some fact about that place and its people intrudes upon the characters’ day. Can players be expected to summon fully rounded characters ex nihilo and be ready with a consistent response to all events, circumstances and people? No. Still less can a GM prepare for all of the consequences of possible player choices. So why even try when what matters is not any objective ‘truth’ but the performance of action - whether that be speech or movement or reaction or even just attitude - in the service of entertainment? To return to my earlier story about magic and trickery, this is the difference between someone having genuinely psychic powers as opposed to ‘cheating’. The outward effect is the same, but only one of them is actually feasible.

There are downsides, of course. There is a certain responsibilty on players and GMs to enter in to and sustain the established fiction of a game world, and part of that is the general maintenance of consistency. This introduces both a broad and a narrow range of potential consequences of ‘cheating’. As with any lie, a basis in truth greatly assists with the upkeep of the deception and so it is important to have some model in mind when describing the game world. Most commonly, in fantasy settings, this is medieval western Europe and so having knowledge of that culure and society to draw upon is extremely helpful. When ambushed by player questions like ‘what do these people eat/wear/do for a living’, a ‘lazy’ GM will have a store of real-world examples to draw from that will feel real even if he or she hasn’t spent a moment actually considering the answers for any particular settlement. Without that vague mental map (or some other drawn from history or media) consistency becomes exponentially more difficult to sustain. More narrowly, if the barber-surgeon NPC you conjured out of thin air last week was called Thomas and this week is called William then that’s a problem and one that is made more likely if you had never given any thought to introducing a barber-surgeon until the moment one of your players expressed interest in their character consulting one. Happily, I can use this example to proffer my sole piece of concrete GMing advice. The solution? Take more notes.